Three Card Poker represents something fascinating in casino game design: a game specifically engineered to balance three competing interests—easy rules, attractive payouts, and substantial house edge. Created by Derek Webb in 1994 and patented in 1997, the game succeeded by satisfying casinos (good profit margins) and players (engaging gameplay with occasional large payouts). But this engineering reveals something crucial: the game’s structure ensures that even optimal strategy produces predictable losses. Understanding why requires examining both the game’s design and the mathematics of how it extracts player money.

Three Card Poker’s genius lies in psychological design. Unlike games like slots where randomness is transparent, Three Card Poker creates the appearance of strategic choice. You receive three cards. You evaluate their strength. You decide whether to bet or fold. This decision-making process feels analytical, not random.

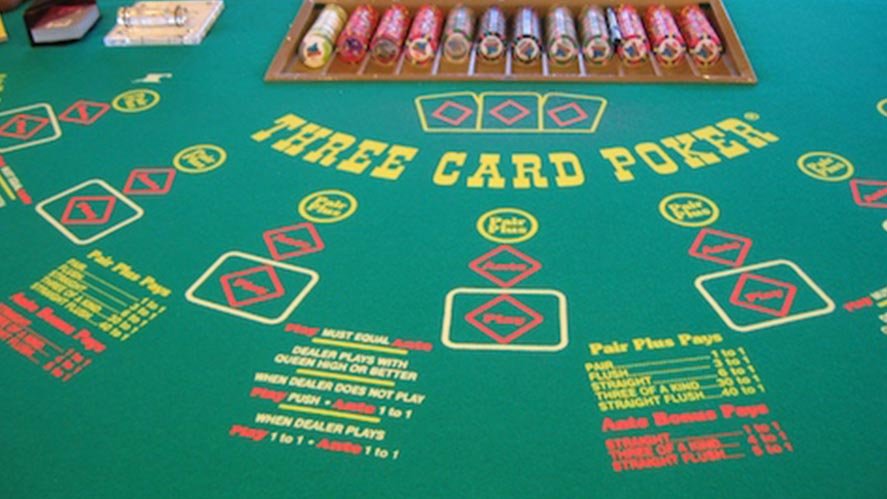

The game offers two independent betting options: Ante-Play and Pair Plus. Ante-Play requires strategic decisions (to call or fold based on hand strength). Pair Plus requires no decision—it’s pure prediction. This dual-bet structure creates multiple engagement vectors. Players who enjoy decision-making can focus on Ante-Play strategy. Players who prefer passive wagering can use Pair Plus. The game accommodates both preferences, increasing its market appeal.

Webb’s original goal involved balancing three variables: easy rules, good payouts, and strong house edge. The game succeeds because it achieves all three simultaneously. New players can learn the rules in minutes. Payouts are large enough to seem generous (5-to-1 on straight flushes, for example). Yet the house edge persists around 3.37% on Ante-Play with optimal strategy, and significantly higher on Pair Plus (around 7.28%).

Three Card Poker’s hand rankings diverge from five-card poker in ways that matter mathematically. Specifically, straights are rarer than flushes and therefore rank higher. This reversal from five-card poker reflects probability: with only three cards, straights become harder to achieve while flushes become relatively more common.

Bonus payments are calculated independently of your win/loss against the dealer. You receive bonus payouts for straights, three of a kind, and straight flushes regardless of whether the dealer qualifies or beats you. This structure creates the illusion that the game rewards skillful identification of strong hands. In reality, bonuses are simply part of the payout table—they’re not additional value you’re earning, but value the casino had already calculated into its house edge.

Three Card Poker instruction repeatedly emphasizes the “Q-6-4 rule”: place a call (bet) only if your highest cards are Queen, 6, and 4 or better. Following this rule reduces the house edge to approximately 3.37%, better than many casino games.

The mathematics behind this rule is sound. By folding weak hands, you avoid the worst outcomes (losing both ante and play bet on hands statistically unlikely to win). By calling strong hands, you leverage good probability. The rule is genuinely optimal; no alternative decision-making approach beats it.

But here lies the paradox: optimal strategy reduces the house edge to 3.37%, not eliminating it. Players who follow the Q-6-4 rule perfectly can expect to lose approximately €33.70 per €1,000 wagered over extended play. This is better than slots (return-to-player typically 85-95%), but worse than blackjack with basic strategy (house edge around 0.5%). Three Card Poker’s “optimal play” remains systematically unfavorable.

The reason relates to how the game is structured. The dealer qualifies with Queen or better. This qualification requirement builds in the house advantage mathematically: you win automatically when the dealer doesn’t qualify, but this happens just often enough that your overall winning percentage still favors the dealer. The payout structure (1-to-1 on ante, bonus payouts on strong hands) looks generous, but the frequency of winning combinations is calibrated to ensure the house edge persists.

Pair Plus bets offer no strategic choice—you simply predict that your hand will contain a pair or better. The payouts appear generous: 30-to-1 on straight flushes, 4-to-1 on three of a kind, 5-to-1 on straights, 4-to-1 on flushes, and 1-to-1 on pairs.

The house edge on Pair Plus reaches approximately 7.28%, more than double the optimal Ante-Play edge. This significant difference reflects a mathematical reality: pairs and better combinations are rarer than many players intuitively assume. You’ll see a qualifying hand in Pair Plus approximately once per seven hands. The generous payouts don’t compensate for the low frequency.

Pair Plus’s appeal lies precisely in its psychological structure: large payouts on infrequent hands create excitement. When you win, you win big. The frequency of losses is high, but they’re small (one unit per loss). This payout structure satisfies the same psychological mechanism that attracts players to slots or lottery tickets: the possibility of disproportionate gain. The house edge reflects this psychological value the casino provides.

Players often combine Ante-Play (lower edge, requires strategy) with Pair Plus (higher edge, no strategy). This combination is perfectly valid, but it’s important to understand the cost: you’re paying a 7.28% house edge on the Pair Plus portion to fund the excitement of potential 30-to-1 payouts. That cost is visible once you frame it explicitly.

Three Card Poker instruction emphasizes comparing paytables across casinos: games paying 5-to-1 on straights and 4-to-1 on flushes have lower house edges than games paying 6-to-1 on straights and 3-to-1 on flushes. This guidance is technically accurate but can mislead.

All Three Card Poker variants carry substantial house edges. Better payoff structures reduce but don’t eliminate this edge. You might find a 3.35% edge variant (better) vs a 3.40% edge variant (slightly worse), but both are systematically unfavorable. Choosing the better paytable is rational optimization within a losing game. But optimizing which losing game to play isn’t the same as finding a game you can beat.

This reflects a broader trap in casino gambling: focusing on relative differences between bad outcomes rather than questioning whether the entire game structure is favorable. It’s reasonable to prefer a 3.35% edge to a 3.40% edge. But both represent systematically losing propositions over time.

Three Card Poker creates the impression of being a “skilled” game. The Q-6-4 rule, paytable optimization, and hand strength evaluation seem to offer analytical leverage. Players feel they’re making strategic decisions, not merely hoping for luck.

This perception is partially accurate but misleading. Yes, strategic decisions exist. Yes, optimal play beats suboptimal play. But the best possible strategy still leaves you losing money systematically. The skill lies in optimizing within constraints you cannot transcend, not in transcending the constraints themselves.

Behavioral economics calls this “narrow framing.” You focus on the immediate strategic question (should I call this specific hand?) without zooming out to the larger frame (I’m playing a game where optimal play produces predictable losses). Narrow framing makes the strategic details feel important. The larger frame reveals that these details matter minimally relative to the game’s structural unfavorability.

Three Card Poker succeeds commercially because it offers something valuable: engaging gameplay with occasional large payouts, accessible rules, and social table play. These are legitimate reasons to gamble. But they’re entertainment values, not investment returns.

A rational approach to Three Card Poker requires separating these values clearly. You might allocate €50 for entertainment and spend it playing Three Card Poker over two hours, knowing that statistically you’ll lose approximately €1.68 from that €50 (assuming optimal play). The €1.68 is the cost of the entertainment. The remaining €48.32 is the value you receive (engagement, excitement, social experience).

This framing is honest. It avoids the trap of believing optimal strategy produces advantage or that your analytical skills matter beyond fine-tuning a losing position. Once you understand that even optimal play carries a 3.37% edge, you’ve learned the essential truth. Everything else (paytable comparison, Q-6-4 application) optimizes the rate at which you lose, not whether you lose.

If you choose to play Three Card Poker:

1. Use the Q-6-4 rule for Ante-Play decisions. This genuinely optimizes your expected value within the game. It’s the correct strategy and worth implementing.

2. Choose better paytable variants when available. If casinos near you offer different payoff structures, prefer games with 5-to-1 on straights and 4-to-1 on flushes. The difference is small but real over extended play.

3. Minimize Pair Plus betting or avoid it entirely. The 7.28% house edge is steep. If you play Pair Plus, keep bets small relative to your Ante-Play wagers.

4. Set strict budgets and treat losses as costs. Decide your maximum loss before playing. View that amount as the cost of entertainment, not money you might recover through skillful play.

5. Maintain realistic expectations about skill. Your decisions matter for optimization, not for reversing the mathematical outcome. Even perfect play produces predictable losses.

Three Card Poker offers engaging entertainment and better odds than many games. But it remains systematically unfavorable through deliberate design. Understanding this design—and refusing to be seduced by the illusion of strategic control—is the key to rational play.